The Agenda 👇

Laetitia Vitaud interviewing Andrew Scott about the “new long life”

What this newsletter, European Straits, is about in 10 ideas

What’s coming in 2021: podcasts, a book club, and more

The new episode of the Building Bridges podcast, brought to you by Laetitia Vitaud, is an inspiring conversation with Andrew Scott about the topic “Age Isn’t Destiny”. Let me quote Laetitia:

I discovered Andrew’s work (and that of his co-author Lynda Gratton) a few years ago when I read their book The 100-Year Life: Living and Working in an Age of Longevity. This book influenced my own work profoundly as I became more and more convinced that increased longevity and the ageing of the population play a huge part in shaping the future of work.

The second book they wrote together was published in 2020. The New Long Life: A Framework for Flourishing in a Changing World is as good as the first. It offers a more practical roadmap for individuals and governments. Adapting to the age of longevity involves all the dimensions of our lives (love, leisure, family life, savings, training, health...). It would be much too shortsighted to be content with just forcing people to postpone retirement.

🎧 You can listen to the whole conversation by using the player above or, if you prefer, on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

I’m lucky to have engaged subscribers who contribute with quite a lot of feedback. For newcomers, however, what this newsletter is all about can sometimes be a bit unclear: What’s this “Entrepreneurial Age”? How does viewing it from Europe make a difference? Is it even relevant for non-Europeans?

For a long time, the whole thing didn’t even have a title! It was just a channel through which I shared personal thoughts about entrepreneurship, finance, strategy and policy—all in connection with my work as a director of my firm The Family.

But as time passed, a few recurring themes, ideas and concepts emerged, and I finally realized that it all revolved around two things:

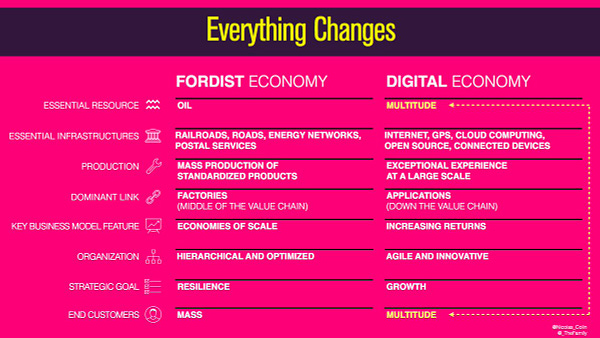

It’s about our economy shifting from the Fordist Age (that of the automobile and mass production) to the Entrepreneurial Age (that of ubiquitous computing and networks).

And it’s about providing a European perspective on this shift—one that I find is missing from the global conversation about tech startups and venture capital 🇪🇺

These, however, can take us in many different directions, and so as we’re entering a new year I thought I would highlight ten ideas that recur in my work 👇

1/ A transition from one paradigm to another

I’ve been describing the current period as a “revolution”, “transition”, or “paradigm shift” since at least 2012. But it was only a few years later, thanks to my friend Bill Janeway, that I discovered the inspiring work of economist Carlota Perez. Absorbing Carlota’s thinking helped me better understand what’s going on in the world from an entrepreneurial perspective. In short, it goes like this:

Every 50-70 years, a technological revolution brings about a new techno-economic paradigm—that is, a new approach to consumption, production and work. It starts with a scientific breakthrough, then it’s accelerated by a financial bubble that eventually bursts, giving way to what Carlota calls the “deployment phase”: the new paradigm gradually spreads out across every dimension of the economy, revealing a new way of life which then requires building a new socio-institutional framework that makes life better for everyone.

Carlota’s system inspired me so much, it now shapes my thinking in every dimension. Here’s an example (although I hadn’t yet settled on Babak Nivi’s concept of the Entrepreneurial Age at the time):

2/ More power on the outside

How can you sum up the Entrepreneurial Age in just one sentence? Quite simple:

In the Entrepreneurial Age, there’s more power outside than inside organizations.

I expanded on that big idea (which has remarkably stood the test of time) in many essays across the years, including this one written in 2018 for the Global Drucker Forum:

What exactly is the nature of that outside power? Today’s power is vested in the mighty “multitude”—the billions of individuals who are now equipped with powerful computing devices and connected with one another through networks.

And it inspires a lesson in strategy and management that every corporate executive needs to keep in mind: the businesses that succeed in the digital economy are the ones that realize how power has been redistributed outside of their organizations.

The winners are not the companies who use the most technology. Rather, they are the companies that best use technology to harness human power, which in turn fuels growth and generates profits.

3/ It's the same pattern across every industry

Most of what I know about how industries are transformed by the current paradigm shift I learned while studying the music industry in 2009. I wrote about it here:

Studying the music industry taught me almost everything I know about a legacy industry shifting to the Entrepreneurial Age. It all started in 2009.

At the time, I was working in Paris in the French ministry of finance. My boss at the Inspection générale des finances (a kind of in-house consulting firm that works exclusively for ministers), knowing that I was interested in technology, offered me a position as the co-chief of staff of a task force formed to ‘save’ the music industry in the face of online piracy.

Then I started to look elsewhere and I realized the same kind of change was happening in every single industry, albeit at a different pace depending on the presence of tangible assets and hardened regulations. This realization led to designing a general framework that I laid out in The Five Stages of Denial (2016). It became the foundation for all my subsequent work on business strategy in the Entrepreneurial Age, which I recently compiled in Shifting Patterns Across Industries.

4/ Capital allocation is key

One big problem in the tech world is that too many people are interested in the technology and not enough people pay attention to what, according to me, really matters when it comes to building successful tech companies: things like design, marketing, sales—and, yes, capital allocation.

I discovered the importance of capital allocation while studying the deformation of industry value chains in the context of the paradigm shift. What I realized is that the tech companies that win excel at capital allocation—case in point: Amazon. Meanwhile, the incumbents that lose do so because they use the wrong financial tools—which Clay Christensen once called “innovation killers”. I wrote about it in Finance: The Secret Key to Becoming a Tech Company (2018):

Now all corporate CEOs and CFOs should adopt Bezos’s playbook. If they don’t want to wake up one morning leading the next GE or Toys “R” Us, they need to take the initiative, focus on the transition as a financial challenge, and redouble their efforts at actually tackling that challenge. No more hackathons, open innovation bullshit, or learning expeditions in Palo Alto, Shenzhen, and Tel Aviv. It’s time to finally open the playbook of corporate strategy in the Entrepreneurial Age and translate it into straightforward and convincing financial terms.

You can discover a compilation of all my writing regarding capital allocation here: All About Capital Allocation.

5/ There's a difference between risk and uncertainty

Why is capital allocation so critical? Mostly because the shift to the Entrepreneurial Age confronts every company, whether new entrant or incumbent, with widespread uncertainty. The problem is that our entire financial reasoning revolves around the notion that allocating capital is about managing risks or hedging against them. And yet there’s a profound difference between risk and uncertainty, as I’ve recently understood thanks to authors such as Vaughn Tan and Jerry Neumann.

I first wrote about it in Country Risk in an Uncertain World (July 2020):

In the past you could confine your business within the limits of the vaguely global part of the economy in which risks could be assessed and managed. Today, the Great Fragmentation is destroying even that “globaloney” corner—starting with Britain, Hong Kong, and even the US—and forcing everyone to realize that uncertainty, not risks, rules the world economy now.

If you’re interested in this topic, I strongly recommend listening to the podcast conversation between Vaughn Tan and my wife Laetitia here.

You can also review a collection of my essays about risk and uncertainty here: All About Risk and Uncertainty.

6/ Venture capital is diffracted

Venture capital matters because it’s the approach to funding businesses that best deals with the uncertainty of our time. Indeed the fact that we’re about midway through the current paradigm shift explains why traditional venture capital is growing in relative terms within the financial services industry.

But there’s another trend at work that has raised my interest: other segments of the financial industry are emulating venture capital more and more.

This whole phenomenon is what I call The Diffraction of Venture Capital (July 2020):

Traditional VC ([Carlota Perez’s] “financial capital”) was fine for funding the installation of the Entrepreneurial Age. But now that rudimentary form of financial capital is in the process of expanding, diversifying, and specializing, which gives birth to a whole new financial services industry whose goal is to serve an ever increasing number of tech companies across various geographies and industries. This marks the rise of “production capital”—and this is causing the current diffraction.

You can discover everything I have written on the topic here: All About Diffracted Venture Capital.

7/ The world is fragmenting

Diffraction on one hand, fragmentation on the other: not entirely unrelated to the paradigm shift is the fact that the world economy is less and less global—what I call The Great Fragmentation.

The fact that crossborder frictions are bound to increase matters a great deal for tech entrepreneurs and investors. We tech people need to understand what’s going on: the Great Fragmentation is happening for both geopolitical reasons and the fact that software is eating the world, entering industries that are structurally more local than global.

It especially matters from my European perspective because this represents an opportunity more than a threat for local tech ecosystems in Europe. The more fragmented the world is, the easier it is to grow local tech champions without necessarily competing with the likes of Tencent or Facebook.

Of course, those successful tech companies that benefit from the Great Fragmentation won’t have a shot at dominating at a global scale; but if such domination has become impossible in general, growing at the continental level is still an optimum—and it’s the new framework within which European tech people must now build.

Read more about it all in All About the Great Fragmentation.

8/ Industrial policy matters

“Industrial policy” is the not-so-fancy word to suggest that governments have a role to play in supporting businesses during the paradigm shift. That’s even more true in a fragmented world where it’s more about every country for itself, so why shouldn’t the government try to make a difference?

The problem is that, like everything else, industrial policy needs to be reinvented for the new age. It can’t be the same policy that contributed to rebuilding Europe after World War II or developing the economies of South Korea and Mainland China from the 1970s onward. A new industrial policy needs to be invented for the Entrepreneurial Age: one that fits the new techno-economic paradigm as well as a more fragmented world economy, to which we’re still not accustomed.

These topics are a frequent focus of this newsletter, you can enjoy an overview here: All About Industrial Policy.

9/ Institutions matter, too

One outcome of a successful industrial policy is the building up of good institutions—ones that support ambitious entrepreneurs while making sure the economy is as inclusive and sustainable as possible. What I see, considering the most recent waves of tech companies entering new industries, is that institutions matter a great deal. In fact, you need institutional innovation by the government, civil society, and the business community itself for tech startups to have a shot at toppling incumbents!

It’s especially true in Europe for at least two reasons.

One, Europe is lagging behind in embracing the new paradigm, therefore it’s now catching up at a stage when it’s less about financial speculation (we’re not in the 1990s anymore) and more about institutional innovation, as seen in industries such as transportation, financial services, agriculture, healthcare, and construction.

Second, for reasons that are both institutional and cultural, the European approach is less focused on the prowess of individual entrepreneurs and more focused on how society needs to change in every dimension. It makes Europe slower when it comes to radical change. But you could argue it’s getting there, albeit with a more multi-dimensional approach.

Institutions are more than regulations: sometimes, it’s simply about precedents, best practices, and customary behavior, and I’ve written about many aspects of them—from the social safety net in my book Hedge to regulating industries in Regulating the Trial-and-Error Economy (2016) to antitrust in this 2018 article published in Forbes.

10/ The view's better from Europe

To this day, the broader history of tech companies is dominated by two nations: the US and China. For a long time, many people even thought it was only about the US. But now that the tech landscape is polarized, it’s become critical to understand what’s happening on both sides: Americans invest a great deal in learning more about China, and the Chinese have been practicing Jiang Zemin’s “go out” policy for quite some time now, learning everything they can from the countries that are racing ahead.

We Europeans have an advantage here: we’re exactly midway between the two from a geographic perspective, and we’re not really sure if we want to pick a side. This provides us with a unique view on the state of technology at the global level, and I’m a firm believer that analysis conducted from Europe can be useful, not only for Europeans themselves, but also for those who, either in the US or in China, are engaged in this race for global tech domination.

I don’t find that there are many newsletters out there offering this perspective for a worldwide audience, and with European Straits, I’m humbly trying to fill that void 😉

If you want to dig deeper, have a look at All About the US-China Rivalry 🇨🇳🇺🇸.

And if you’re not a subscriber yet, please consider today’s special offer: £99 for an entire year instead of £150! It’s on until next Sunday (January 10) ⏰

Just a few words about the coming expansion of European Straits. On top of the essays and syndicated podcasts, this is what I’m about to launch in the coming week:

My own podcast, with the primary focus of interviewing non-Europeans on technology and startups in Europe. It will be published here, alternating with the Building Bridges podcast.

A book club: I intend to share insights and thoughts about a book I’ve read at least once a month—only for paying subscribers, though.

And many other things that are still in preparation for 2021.

Don’t forget that you can also find me in Sifted (where I write two columns a month), Nouveau Départ (in French 🇫🇷—with my wife Laetitia), Capital Call (where I curate what European venture capitalists think, in their own words, with my friends Willy Braun, a cofounder of Daphni, and Vincent Touati-Tomas of Northzone), and in my firm The Family’s newsletter, where I write the occasional short essay for ambitious tech entrepreneurs around the globe.

From European Startups as an Asset Class (February 2020):

Asset allocators are following a known and safe playbook by overlooking European startups (like Christensen’s integrated steel companies). But that then becomes an opportunity for new (disruptive) allocators (Christensen’s minimills) who are willing to make an early bet on these “lesser” startups, grow from there, and then eventually compete with established players for the best, most lucrative deals at the high end of the startup market in Silicon Valley.

All recent editions:

A Few Notes on Israel 🇮🇱—for subscribers only.

COVID-19: A Retrospective—for subscribers only.

All About Industrial Policy—for everyone.

All About Capital Allocation—for everyone.

All About the Great Fragmentation—for everyone.

All About Risk and Uncertainty—for everyone.

All About Diffracted Venture Capital—for everyone.

All About the US-China Rivalry 🇨🇳🇺🇸—for everyone.

The Uncertainty Mindset w/ Vaughn Tan. Automation creating jobs. Financial loops. Industries shifting. Most read essays.—for everyone.

Shifting Patterns Across Industries—for everyone.

My 10 Most Read (Paid) Essays This Year—for everyone.

European Straits is a 5-email-a-week product, and all essays are subscriber-only (with rare exceptions). Join us for £99 instead of £150 (until Friday, January 8)!

From Munich, Germany 🇩🇪

Nicolas

My Worldview in 10 Ideas