Hi, it’s Nicolas from The Family. Today, I’m discussing the various governmental responses to the economic and social crisis triggered by COVID-19—and why we should focus on helping individuals.

⚠️ The paid version of European Straits launched three weeks ago! In addition to this free edition, my paying subscribers receive a Monday Note as their work week is about to begin and a set of Friday Reads that dig deeper into various topics related to investing in tech startups, especially in Europe.

Obviously no problem if you haven’t subscribed! Still, here’s what you’ve missed lately:

An analysis of the impact of the COVID-19 crisis for startups and how to analyze government-led responses, inspired by Ventures Hacks’s Babak Nivi: Quality and Scale, Simultaneously.

A 10-point framework to help investors assess their portfolio of tech participations and decide on allocating capital in the context of the crisis: COVID-19's Impact On Your Portfolio.

My take on how venture capitalists are adapting to the new COVID-19 context: Venture Capitalists and the Choices They Make.

If you don’t want to miss the next paid editions, it’s time to subscribe! In the next Friday Reads, I will share a few thoughts on how the COVID-19 crisis transforms tech ecosystems from a VC point of view.

As for today, I’d like to focus on how to address the economic consequences of the COVID-19, insisting on the importance of supporting individuals 👇

1/ The idea of the state salvaging the economy with massive public spending is not that old. Back when laissez faire was the rule – that is, for most of the 19th century – it was considered unwise for the state to intervene in the economy. And even if it had tried to do so, the state’s firepower was not as large as it is today: in 1908, public spending represented only 2.59% of GDP in the US, 8.41% in the UK, and 13.03% in France!

What changed between then and now? Two things, mostly:

World War I triggered a massive increase in public spending. Western governments had to raise lots of taxes to support the war effort, and those spending levels never really came down afterwards. Both in the US and France, a national income tax was introduced to increase government revenue in the context of the war. It only went up after that.

Then John Maynard Keynes, the brilliant economist from Cambridge, provided government leaders with a compelling intellectual framework for allocating public resources to counter the consequences of economic crises and boost economic growth. From the 1930s onward, Keynesian economics replaced laissez faire in the minds of those designing economic policy.

2/ That new economic thinking was battle-tested in response to the Great Depression. In the US, it took the form of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. The whole effort, which was much more complex and nuanced than what pop history would lead us to believe, is an interesting precedent because the context was so similar to the situation we’re in today:

The rise of a new techno-economic paradigm had led to a distorted allocation of resources. The Roaring Twenties had been marked by the fast growth of mass manufacturers, an equivalent to today’s tech companies. Meanwhile, corporations born in the previous paradigm (that of steel and heavy engineering) had long reached maturity and were able to pay hefty dividends to their shareholders. Both trends had contributed to fueling a bubble on the stock market.

When the bubble burst, the aftermath was a reduction in purchasing across the board. The dire economic conditions led everyone – households at every level of income and businesses – to delay purchasing goods and services, thus forcing labor-intensive businesses to lay off workers, which in turn contributed to depressing demand even more.

This was done in the context of higher barriers to immigration (the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act of 1924) and higher trade tariffs between the US and Europe. As written here, “this charged a high tax for imports thereby leading to less trade between America and foreign countries along with some economic retaliation”. Sound familiar?

3/ And so can the New Deal serve as an inspiration for responding to today’s crisis? In fact, there were two New Deals. The first, which mostly failed, was a corporatist program to end deflation and raise prices by restricting supply. The second was the result of Roosevelt deciding to move leftward in preparation for the 1936 presidential election. Its landmark achievements were the Wagner Act, which established collective bargaining between employers and labor, and the Social Security Act, which set up the first federal social insurance regime to cover risks such as old age and unemployment; there were also tightening regulations in the financial services industry and various other interventions by the state.

There are three lessons that I think we could draw from the Second New Deal:

Most of it was seemingly on supporting demand. Pensions and unemployment benefits were designed to support demand. Providing jobs in the public sector and building new infrastructures were also about supporting demand.

However, supporting demand immediately translated into supporting supply. To quote my book Hedge, “Whenever consumer demand went down, businesses had to close factories and fire their workers, fueling unemployment, poverty, and anger in the process. If they did keep their employees on the payroll, the risk was producing too much and only delaying hardship instead of preventing it.” Sustained consumer demand was critical for capitalist enterprises to survive.

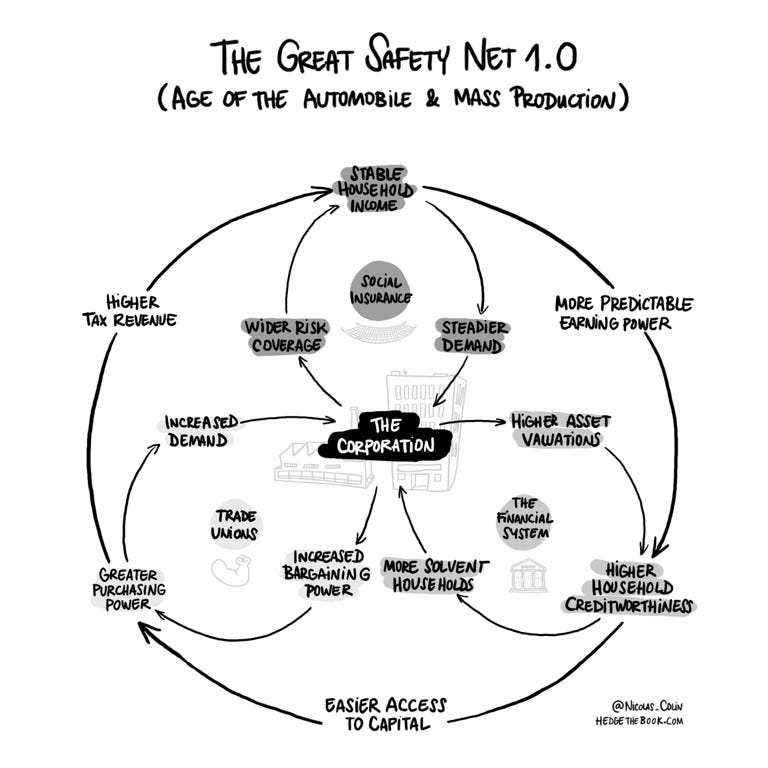

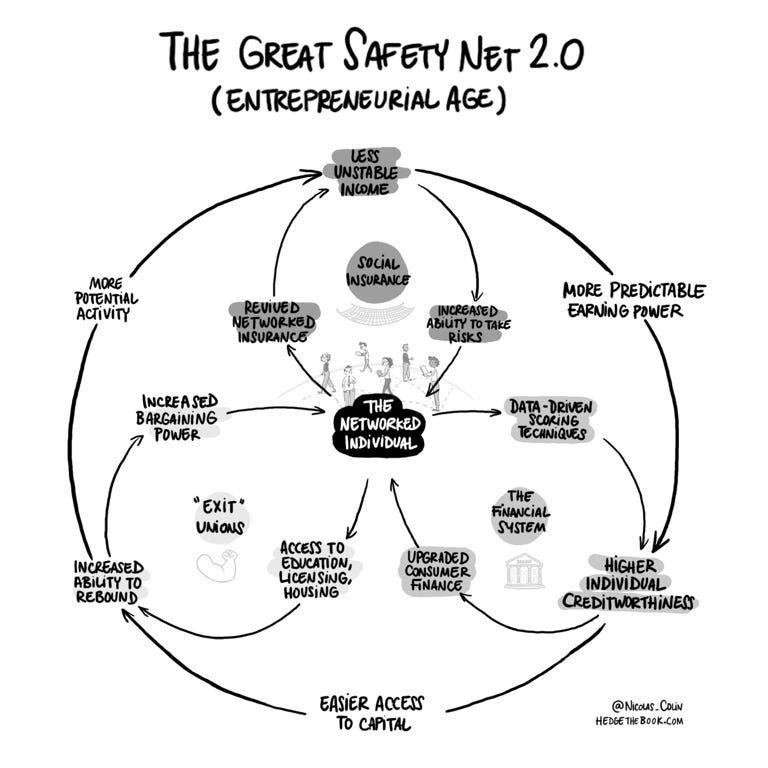

Then certain institutions were put in place to make sure that the government would only have to intervene once, with the mechanism then being self-sustaining. This idea of a virtuous cycle linking the demand side and the supply side thanks to well-designed institutions is summed up by my concept of the “Great Safety Net” (basically, social insurance regimes + consumer finance + collective bargaining).

4/ If we admit that we’re in a crisis similar to the Great Depression (mass unemployment + free-falling stock market + depressed consumer demand), there are two sets of questions that need answering:

How do we distribute our efforts at tackling the crisis between the demand side and the supply side? Like at the time of the New Deal, should we support consumer demand as a path to supporting the supply side?

What institutions should we put in place so that inclusive economic growth becomes self-sustaining and the economy ends up in an even better shape once we’re out of the crisis? I call this new set of institutions the “Great Safety Net 2.0” (see below).

5/ Clearly, one goal should be to prevent demand from collapsing, lest it bring the entire economy to a halt, as explained in this New York Times article by Neil Irwin:

One person’s spending is another person’s income. That, in a single sentence, is what the $87 trillion global economy is.

That relationship, between spending and income, consumption and production, is at the core of how a capitalist economy works. It is the basis of a perpetual motion machine. We buy the things we want and need, and in exchange give money to the people who produced those things, who in turn use that money to buy the things they want and need, and so on, forever.

What is so deeply worrying about the potential economic ripple effects of the virus is that it requires this perpetual motion machine to come to a near-complete stop across large chunks of the economy, for an indeterminate period of time. No modern economy has experienced anything quite like this.

The conclusion is straightforward: we need to put money in the hands of consumers. Like with the Second New Deal (the one that worked), the first step should be all about supporting individuals.

6/ But then how can we make sure that supporting demand helps the supply side? This is where it gets tricky for at least three reasons:

First, it’s hard for consumers to spend money during a lockdown. There are entire industries, starting with restaurants and mobility, that simply can’t serve consumers in the context of social distancing, no matter how much individuals have to spend.

Second, we’re in a different techno-economic paradigm now. The Great Depression happened at the dawn of the age of the automobile and mass production. The COVID-19 has struck as we’re entering the Entrepreneurial Age. And so we have to figure out how supporting demand will translate into a thriving business world in this radically different context.

Third, most people have more financial obligations on top of their immediate consumption. And so the money you put in their hands will likely be used primarily to repay debts rather than to consume goods and services. This makes the current situation rather different from the 1930s: the “Great Safety Net 1.0” has succeeded in that it makes it possible for most individuals to borrow so much money! Here’s Noah Smith:

The economy isn’t defined only by real activity; it also is made up of a web of financial obligations. People owe rent, utilities, student-loan payments, auto payments, mortgage payments, property taxes and many other monthly bills even if they’ve been laid off or furloughed. Companies owe debt-service payments, rent and so on. As economist Larry Summers puts it, “economic time has been stopped, but financial time has not been stopped.” Financial obligations alone are a large share of disposable income.

7/ The idea that immediately comes to most politicians’ minds when dealing with a crisis is to rescue the manufacturing sector—like happened following the financial crisis in 2008 with the American auto industry. There are three reasons why government support was so focused on manufacturing in the past:

The downside of not supporting manufacturers is huge because those businesses have high fixed costs and sunk costs. Why waste all those investments because the economy is doing badly for a brief period? (The same reasoning applies to airlines, cruise ship companies, and shale frackers.)

The upside of supporting manufacturing companies is high because those businesses have increasing returns to scale. It’s not because they employ the most workers (that has never been true). Rather, it’s because their survival supposedly creates immense value over time: those companies used to be able to create a substantial economic surplus that could then be redistributed to the rest of the economy through a well-designed social contract.

Most importantly, the nature of those corporations used to make them the ideal proxy for deploying the institutions forming the “Great Safety Net 1.0”. Hence the fact that the big manufacturing corporation, “the single greatest risk-mitigating institution ever” as once written by Adam Davidson, is at the center of the graph above. Not only did manufacturing create a massive economic surplus, it was also the foundation for building the social contract of the Fordist Age.

8/ Are those arguments still valid today? Let’s start by examining downside protection. A rationale for supporting businesses in a time of crisis is to make sure that the fixed costs and sunk costs that a given business represents are not lost forever. Today, this is still valid for manufacturing businesses, but we can’t stop there anymore:

We could help tech companies due to their high fixed costs (including some that are still at the startup stage). Their operations represent such an investment that it’s worth including them in the picture when designing a governmental effort at salvaging the supply side. This calls for designing new policy instruments for a different breed of business.

We could help businesses in proximity services to compensate for the fact that consumers cannot use their product during the lockdown period. Have a look at this overview by JPMorgan that reveals that 25% of small businesses hold less than 13 days of cash reserves—and that the median for small restaurants is just 16 days!

Finally, we should help individuals not only as consumers, but also as asset owners. Indeed, unlike in the 1930s, now individuals, alongside businesses, also bear high fixed costs, and it makes them especially vulnerable in the current period. There’s no reason why any individual should lose their car, their home, or their excellent credit score because the economy is doing badly for a brief period of time. Yet another reason to focus on individuals!

9/ Now on to the upside preservation. As I wrote in a past issue titled Does Manufacturing Matter?,

[In the Fordist Age,] assembly lines emerged as the segment of the productive economy generating superior increasing returns to scale: the larger those assembly lines were, the more productive they became (up to a certain point, of course)

[However,] manufacturing isn’t the only sector blessed with increasing returns to scale anymore. Today, increasing returns to scale are much more powerful down the stream, where tech companies interact with networked individuals, than they are along assembly lines up the stream. And so manufacturers have been out-powered by tech companies, no longer generating the biggest economic surplus in the economy.

I can’t stress that message enough. In the Entrepreneurial Age, future economic surplus is best maximized by supporting what now forms the core of value creation: tech companies interacting with networked individuals. This calls for focusing on tech companies, but also for doubling down on supporting individuals. The upside of doing so is greater these days because individuals are so much more than consumers and borrowers: as part of networks, they contribute a great deal to value creation in the Entrepreneurial Age through network effects.

10/ Finally, how can we use the government’s response to the crisis to deploy the new institutions that will maximize economic security and prosperity in the future? To make it short, my view is that the networked individual, not the big corporation, is now the center of our economy. And that’s just another argument for supporting individuals. Governments should support them with more cash throughout the crisis. But they should also focus on them when the time comes to design a new set of institutions—a new social contract so that inclusive economic growth becomes self-sustaining again once the crisis is over 👇

💻 Like all companies and individuals around the globe, my firm The Family is making lots of changes due to the current crisis. We're concentrating on our key value proposition: supporting entrepreneurs who are growing their businesses. We've also redesigned our website to include resources specifically aimed at the crisis (including a hotline entrepreneurs can use to have a call with our Fellowship Directors Balthazar de Lavergne and Mathias Pastor).

🦊 Our events are back as well, 100% online thanks to our friends at Hopin. Every weekday at 12:19 pm CET, my cofounder Alice Zagury is talking with one of our portfolio entrepreneurs about both their entrepreneurial journey and how they're handling the crisis. Then on Friday we're hosting an all-day Remote Summit focused on the best practices in the world of remote work, which we’ve all now been plunged into And on Saturday morning, we're hosting a meetup where people can potentially meet their new cofounder! Join us 🤗

🇫🇷 Finally, for those of you who read French, have a look at this interview (my wife Laetitia Vitaud interviewing me for Welcome to the Jungle, a media focused on HR): it’s a wide-ranging discussion covering the impact of the crisis on tech startups, the radical upheaval of the labor market, and the various government responses across Europe: Les crises ne sont pas que des problèmes à régler, elles sont aussi des opportunités de redistribuer les cartes.

The comprehensive reading list attached to the European Straits weekly essay is part of the Friday Reads paid edition. Subscribe if you want to receive that list on Friday!

From Normandy, France 🇫🇷

Nicolas