VCs: Would You Rather Be Yahoo or Google?

Today: Recent discussions about risk-adjusted returns in VC; Taleb’s tail-risk hedges; will you be Yahoo or Google?

The Agenda 👇

Maybe VCs should diversify across larger portfolios

Or maybe VCs should purchase tail-risk hedges

More diffraction: the BlackRocks and Vanguards of VC

Imagine it’s 1999. Would you rather be Yahoo or Google?

An article about venture capital made the rounds last week: The Pervasive, Head-Scratching, Risk-Exploding Problem With Venture Capital (by Kamal Hassan, Monisha Varadan & Claudia Zeisberger in Institutional Investor). It’s making the case that limited partners should make an effort at diversifying if they want venture capital to resemble an investment-grade asset class:

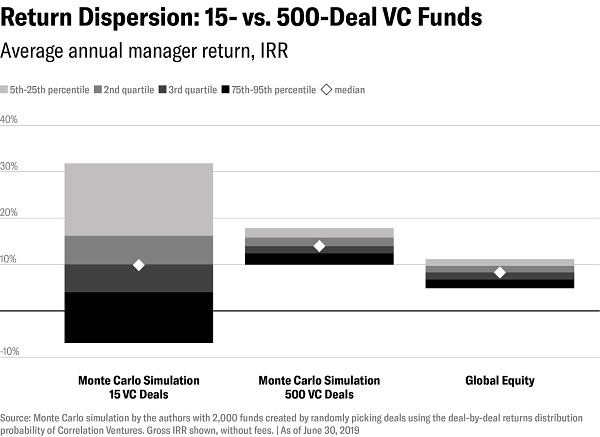

The simulated VC portfolio of 15 investments behaved very similarly to the real-life VC fund returns depicted in the first chart. There is a large dispersion between the top- and bottom-quartile funds, with a median return of around 10 percent. Bottom-quartile funds lost money, and the top quartile has its own large internal dispersion.

[But] with the recommended portfolio size of 500 investments...the dispersion for the VC portfolio returns tightens to a range of 10 to 17 percent. This range of returns from bottom to top quartile is similar in size to that of public equity funds. With suitably high diversification, VC indeed becomes an investment-grade asset.

This was stressed by venture capitalist Rob Leclerc in this tweet:

Using my own words, the message here is that LPs are too picky when deploying capital. They tend to stick with just a few firms, investing in their funds year after year rather than trusting a higher number of partnerships that invest across various geographies and sectors.

Diversifying (reaching a portfolio size of at least 500 companies) would tighten the dispersion of returns and make venture capital returns more consistent across time and more predictable. In other words, it would make much more sense from an institutional investor’s perspective.

Why isn’t it happening? Two reasons mostly:

First, VC represents too small a fraction of the total allocation for any institutional investor. In the podcast conversation I linked last week with Carlos Espinal of Seedcamp, Thomas Kristensen of LGT Capital Partners (a shareholder in my firm The Family) mentions that private equity typically represents 10% of an institutional investor’s allocation, and that VC typically represents 10% of the PE allocation—that is, 1% of the total allocation. In other words, it’s not much, and there’s no reason to think that LPs are really seeking diversification on that very small fraction of the total capital they’ve deployed.

Second, venture capitalists themselves are not incentivized to promote that kind of diversification with their LPs. This is explained in the Institutional Investor article:

There are no rewards for diversification as a venture GP. Today’s investors flock to top-quartile managers, who must act in a risky manner to overachieve. Such GPs often insist that their portfolios must stay small to “not dilute their winners.” In other words, they rely on picking winners, but inadvertently admit to not being able to do so consistently.

Managers who reduce risk by diversifying will, by definition, at best achieve second-quartile returns. Only the top quartile is rewarded, through performance and management fees on larger follow-on funds. Given the ten-plus-year life of each fund, and the way capital floods to proven winners, it is economically rational for a GP to take a risk at getting lucky with an undiversified fund rather than diversifying — knowing that diversifying would result in fewer if any rewards.

This is especially true since most GPs show signs of overconfidence about their abilities, and trust that they will outperform, believing it will happen through skill, not luck.

And indeed you will find GPs that are clearly skeptical when it comes to diversification, such as Hussein Kanji of Hoxton Ventures:

Yet, as Hassan, Varadan & Zeisberger point out, the case for diversification is corroborated by recent discoveries by the AngelList research team (led by Abe Othman):

We found that investors could benefit from indexing as broadly as possible at the seed stage, by putting money into every credible deal, because any selective policy for seed-stage investing—absent perfect foresight—will eventually be outperformed by an indexing approach.

We did do some simulations on what indexing at seed actually looks like over human timescales. Over a ten-year investment window, indexing beats 90-95% of investors picking deals, even when those investors have some alpha on deal selection. So the idea that there are some terrific seed investors that soundly beat indices is not inconsistent with our results.

Interestingly, reading about indexing/diversification in VC made me think of another article published in Institutional Investor only a few days earlier. It’s about Nassim Nicholas Taleb and Mark Spitznagel’s approach to providing a tail-risk hedge to institutional investors so as to enable them not to diversify.

That’s because, while it reduces risk, diversification comes with a price:

Taleb countered that with an argument that is essentially the central argument of tail hedging and risk mitigation. Meng didn’t tell viewers of the webcast what the hedging strategy cost the plan in previous years. “I don’t know if you realize that these strategies need to be weighed against what they made or lost before that,” Taleb said.

“Effectively, we think, back-of-the-envelope calculation, the so-called mitigating strategy would have lost something like $30 billion the previous year. So you make $11 billion, you lose $30 billion before, not a great trade. It’s definitely not a great trade over long periods of time, when you lose in rallies and make back a little bit in the selloff,” he said.

Taleb believes that the same flawed logic is why investors lose billions of their savings every year. They’re relying on strategies like diversification that the financial industry has long peddled to protect investors’ downside. But adding assets such as bonds, or even gold, costs investors in bull markets, without fully cushioning portfolios in a crisis.

And so the question here is: instead of seeking that diversification that goes against everything that venture capital GPs stand for, why not decide that you’ll keep on trying to pick winners, and then purchase a tail-risk hedge of some sort in case you made a mistake (or in case a Black Swan derails your allocation strategy?). I’ll have to reflect a bit more on that one but at this point I have two ideas in mind:

Is there such a thing as tail-risk in venture? It definitely exists on the stock market, where volatility can be high. But VC is about illiquid assets that you need to hold for so long anyway that it’s hard to lose it all in an instant. I really don’t see any precedent in the current paradigm shift, except maybe for the dotcom bubble bursting 20 years ago. (But we’re talking about the one inflection point in Carlota Perez’s model there, not about something that’s bound to happen every 3-4 years or so.)

On the other hand, I like the idea of timing investments to the market based on how far we’ve gone in the paradigm shift in a given industry (check out At What Stage Should You Invest in European Startups? and A Thesis For Sector-Focused Hedge Funds). And so I would say you could definitely design a tail-risk hedge that’s focused on one industry only, and covers LPs against volatility should any Black Swan event contribute to suddenly halting the shift to the Entrepreneurial Age in a given industry.

In any case, here’s what I think is bound to happen—and it’s consistent with the thesis on the Diffraction of Venture Capital. The market will get more and more polarized between two extremes:

On one end will be the GPs that retain a craftsmanship approach to venture investing, and the LPs that are content with bankrolling them—basically everyone that believes that things “happen through skill, not luck”—or through what Ashby Monk calls “structural advantages” (see his Mortal Inspiration from the Gods of Venture Capital). It’s the equivalent of active investing on the stock market: not the largest share, but one that contributes key insights.

On the other end will be those players that embrace a more industrial (large-scale) approach to the whole game. Not only are they already in the process of abandoning the craftsmanship approach of traditional venture capital, at some point they’ll explore large-scale approaches such as diversification (as recommended by Hassan, Varadan & Zeisberger) or tail-risk hedge (as recommended by Taleb and Spitznagel).

What’s interesting is that the players already exploring the latter approach are those that are traditionally focused on the earliest stages and as a result don’t have that much capital under management—the likes of 500 Startups and Y Combinator (and, yes, The Family). You could say they don’t appear as if they’re about to become the dominant players in the financial services industry. Yet at the same time, scaling up their current approach would definitely turn them into the new BlackRocks and the new Vanguards—the new passive investors in a financial services industry eaten by VC.

It’s less flashy than the proud stock pickers, but it’s also much, much larger and it comes with an outsized influence over the entire market.

I’m not really sure if it flies as a comparison, but it made me think again about Halt & Catch Fire—specifically the last season, in which Joe MacMillan and the others are competing in the emerging field of online search. We all know who won that war: Google (the search engine powered by an algorithm), not Yahoo (the web portal filled out by humans). But at the dawn of the World Wide Web, it was rational to build a web portal rather than a search engine, because the Web was still too small for a dumb search algorithm to add any value as compared with real humans indexing the Web page by page.

And these days it’s (still) logical to raise a traditional VC fund that invests in 10-15 companies rather than pursuing the crazy diversification approach with exposure to a portfolio of 500+ companies, because the tech world still seems too small for a diversified approach. But will that last? Or will software eat the world, after all?

So, if you’re a VC, imagine your market is online search and it’s 1999 (Yahoo was founded in 1994 and Google was founded in 1998). Which one would you rather be? Yahoo (the active investor of online search) was still the dominant force back then, and it had quite a wild ride; but in retrospect, it seems obvious that you should have backed Google (the passive investor).

Or, if you’re an LP, maybe, just maybe, you should have backed both?

😀 The Great Fragmentation. I love this tweet by Benedict Evans. Such a great summary of what’s currently happening in the tech world:

🙂Africa might be the next frontier. Interesting that Netflix is betting on it with a mobile-first approach for distributing original content: Netflix Bets on Mobile Blitz to Strengthen Africa Foothold. (Meanwhile, on the French front: If you’ve been to France, steer clear of Netflix’s dire comedy Emily in Paris.)

😏 Libertarians, especially in the US, like to hate the European Union because it supposedly regulates too much. Meanwhile, it also guarantees its citizens the right to travel and work in 27 countries without many constraints, as we’re reminded by The Economist in The problem of the EU's “golden passports”.

😐 Product integration. A very long time ago, I wrote a piece (in French: Facebook, application immobile) to praise Facebook’s decision to unbundle Messenger from the Facebook app. Now they’re reversing this decision, as explained in Facebook is melding its mega apps together: Inside 'interop'.

😒 It turns out China, too, has antitrust authorities (you might remember I was asking myself that question some time ago). And just like us Westerners, they’re using political and geopolitical motivations, now going after US tech giants: China preparing an antitrust investigation into Google.

😖 “Trump can’t protect himself, therefore he can’t protect America”: in my opinion, Biden only has to repeat this over the next 4 weeks, and he’ll win in a landslide. Also this Tweet by Ian Bremmer is more or less true, which is rather shocking:

If you’ve been forwarded this paid edition of European Straits, you should subscribe so as not to miss the next ones.

From Normandy, France 🇫🇷

Nicolas